What is intelligence?

Can we do better than "you know it when you see it"?

[ Welcome! This is my first post. Thanks to Asterisk Magazine for supporting this blog post as part of their AI Fellows program. Thanks especially to Avital Morris, Clara Collier, and Jake Eaton for helping us figure out the esoteric art of blog writing. ]

Whatever intelligence is, it seems important. We praise kids for being smart, and doing hard things like winning math olympiads and spelling bees. We look up to mathematicians that resolve centuries-old conjectures, people that can quickly remember hundreds of digits and the order of several decks of cards, and creatives that write beautiful symphonies or create stunning paintings. Many people think that being smart has something to do with how successful you will be in life; despite widespread disagreement over how much intelligence matters, a lot of people still work hard to make themselves smarter (for example, by taking classes), or to at least be perceived as smart.

Beyond everyday life, tech companies like OpenAI and Google are currently investing eye-watering sums of money to create performant artificial intelligence (AI). There is so much money being thrown around that even scrappy startups promising to make super smart AIs are making bank. Even non-tech companies are investing heavily in AI, hoping that they can use it to improve productivity, for example by automating mundane tasks.

People like to point out the failures of advanced AI models like ChatGPT, including difficulties with counting and spatial reasoning, and tendencies toward extreme sycophancy. But many people remain excited by the ever-increasing capabilities of these systems. Some people even think, given how important and useful intelligence apparently is, that systems like these might eventually become so smart that they kill us all.

All of this is just to say that some people care quite a lot about intelligence. But what is intelligence, anyway?

Against non-definition

I recently attended a talk by AI researcher Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, who is “(in)famous” for being one of the people that invented diffusion models. The talk was colorfully titled “Advice for a young investigator in the first and last days of the Anthropocene”, and was about how researchers ought to adapt their behavior given large improvements in AI capabilities that might be on the horizon. In particular, you probably shouldn’t focus on scientific questions that are expected to be trivial for next year’s AI models.

(It was interesting to note the apparent cultural differences between Bay Area AI researchers and the Harvard academic researchers that attended the talk. Jascha said that a lot of the people he knew had very short “timelines”, meaning that they expect AI whose capabilities match and/or exceed those of humans to appear within the next two-ish years. A lot of the people in the audience, including many people I know, have somewhat longer or much longer timelines. Who’s right? Let’s leave this obviously hard and fraught question for a future post; I don’t want to get into it here.)

An important point Jascha made early in the talk is that we don’t need to be able to precisely define intelligence in order to see that frontier AI models are getting better and better. He used flying as an analogy.

The analogy goes something like this. The Wright brothers famously built the first planes1, and made major strides between 1903 and 1905. First, they just experimented with gliders; later, they could fly their gadget for tens and then hundreds of feet; and soon enough, the duration of their flights could be measured in tens of minutes (or longer) and tens of miles (or longer). Around ten years after their planes starting getting good, airplanes became capable enough that they played a major role in the first World War.

At no point did the Wrights need to precisely define flying. And moreover, it probably would not have helped them. People could (and did, I think) quibble about the extent to which their gadgets could ‘really’ fly. They obviously couldn’t fly as long as birds can, and also lacked the same intricate control over their movement. They were unwieldy and dangerous. There were limits to how high they could go, how fast they could go, and how well they could land. So did it ‘count’? Did the Wrights and their contemporaries really achieve the Platonic ideal of flight?

Well, who cares? Nowadays we have crazy and expensive fighter jets that break the sound barrier multiple times over, and giant planes that can take you across an ocean in just a few hours. By now, we have clearly achieved ‘artificial general flight’, however you define it.2 This is true even if “flight” is hard to define, and if our artificial version of it looks quite a bit different than how birds do it. The lesson is that, even if you can’t define “flight”, you can still look up in the sky and say, “Oh ****, look at that thing go!” And that still counts as progress!

Similarly, Jascha’s argument goes, we can recognize that frontier AI models are getting better and better, even if we can’t precisely define “intelligence”. And maybe it isn’t that helpful to define “intelligence” anyway. If you say that feat X achieved by model Y doesn’t really count as evidence of intelligence, but only because we can’t precisely define the word “intelligence”, then you’re probably just being a contrarian troll.3

I think Jascha’s argument is reasonable. There’s certainly a lot of contrarianism about recent progress in AI, with the worst flavor of it being “as-if”-ism. Models behave as if they understand what you’re saying, and can provide appropriate responses, but this is an illusion. They don’t really understand, deep down, somehow. AI models simply can’t be intelligent in the way that humans can, since the brain is not a computer, or AI models lack intentionality, or whatever other dumb objections philosophers come up with.

Nonetheless, I still think it’s worth taking some time to try to define “intelligence”. I think we gain clarity about what we’re looking for, and what we care about, by trying to be more precise about it. Attempting to grope towards a working definition helps us sift the interesting and actionable questions regarding intelligence from what are effectively philosophical concerns. (An example of the latter: can machines think?) Our definition doesn’t have to be perfectly precise—just useful.

What counts as intelligence?

One way to operationally define intelligence is to say that we know it when we see it. But that’s the coward’s way out, so let’s try to do better than that.

Another way to define intelligence is via some sort of threshold. These things count as truly intelligent, and those things don’t. We often effectively do this in everyday life, by using “intelligence” to refer to smart people and their smart people feats, like proving difficult mathematical theorems and writing cerebral works of philosophy. Other things, like doomscrolling on your phone, are not regarded as intelligent. This view also underlies at least one interpretation of the Turing test: if a machine talking to us through a chatroom (or via some other reasonable means) were smart enough to convince us that they are also human, regardless of how incessantly we question them, then it would be sensible to view them as comparably intelligent to humans.

In any case, I really don’t think we should define intelligence in terms of a threshold, for two basic reasons: it’s hard to know what the threshold should be, and it isn’t clear to me that drawing a categorical distinction between “intelligent” and “unintelligent” is useful.

Many things we might not naively consider as intelligent, like our ability to stand on one leg, or recognize a friend’s face, have been found to be quite computationally difficult to achieve—and hence, intelligent in at least that sense. Humans are good at tasks like seeing and recognizing objects not because those tasks are easy, but because specialized neural circuits and a lot of brain real estate are devoted to them. We know this partly because it took a while to build good image classifiers, partly because there exist neurological disorders in which this machinery is disrupted, and partly because neuroscientists have spent around a decade modeling (nontrivial chunks of) the primate visual system.

The insight that things that are easy for humans might not be easy for every possible intelligent agent is sometimes called Moravec’s paradox, after the robotics researcher and futurist Hans Moravec. Being able to recognize the face of your friend is intelligent; being able to walk without falling over is intelligent; being able to understand a stupid joke and laugh at it is intelligent. Even doomscrolling on your phone, which requires (at least small amounts of) attention and the dexterous manipulation of a handheld device, is intelligent.

You might say: fine, we should be careful about where we draw the line, so that capabilities like “walking” and “doomscrolling” are safe. But shouldn’t we draw the line somewhere? This brings me to my second basic reason for not drawing a line: how would it help us?

Most of the signs of intelligence we’re familiar with can be quantified in terms of continuous performance measures. Even if you can’t prove Fermat’s Last Theorem in full generality, maybe you can prove a special case of it (like n = 4). Even if you can’t prove any cases of Fermat’s Last Theorem, maybe you know some basic number theory, and can solve simple Diophantine equations. Even if you can’t do that, maybe you know what integers are and how to count. Even if you can’t do that, maybe you can at least see a number-shaped thing on the page in front of you, and associate its shape with the word “number”.

This is true even of things that seem very all-or-nothing, like your ability to beat a hard video game. Sure, you can either win (R = 1) or lose (R = 0), but it’s also sensible to track how your probability of winning changes over time, or how your overall score changes (in games with point totals), or how many levels you can beat so far, or how well you’ve mastered relevant subtasks like moving and defeating enemies. Even if we associate “intelligence” with being able to do something, there is almost always a non-binary way to measure how well you can do it; we can be a lot more granular than “can do it” versus “can’t do it”.

I think “intelligence” is best understood as a matter of degree rather than as something that is present or absent. This admittedly leads to an incredibly permissive notion of intelligence, since it means machines are intelligent, animals are intelligent, and even single cells are (at least to some extent) intelligent. I think that’s fine; I’m not saying all these things are on the same footing in all respects, just that they all have characteristics that we might consider as reflecting intelligence. In other words, almost anything you can think of is intelligent to some extent—so almost anything ‘counts’—but this does not mean that all forms of intelligence are equally capable or interesting.

Unfortunately, I still haven’t really defined “intelligence”. I’ll start doing that in the next section. But before I go on, I want to make one more comment about using thresholds to define intelligence. (Read: I want to complain about something.)

People sometimes do this in a dumb contrarian way, and define intelligence as whatever it is that AI models can’t currently do. Sure, AI models can classify images and play Atari games, but they can’t (yet) prove Fermat’s Last Theorem by themselves or write beautiful symphonies. The latter kinds of things, this line of thinking goes, comprise what we truly mean by intelligence.

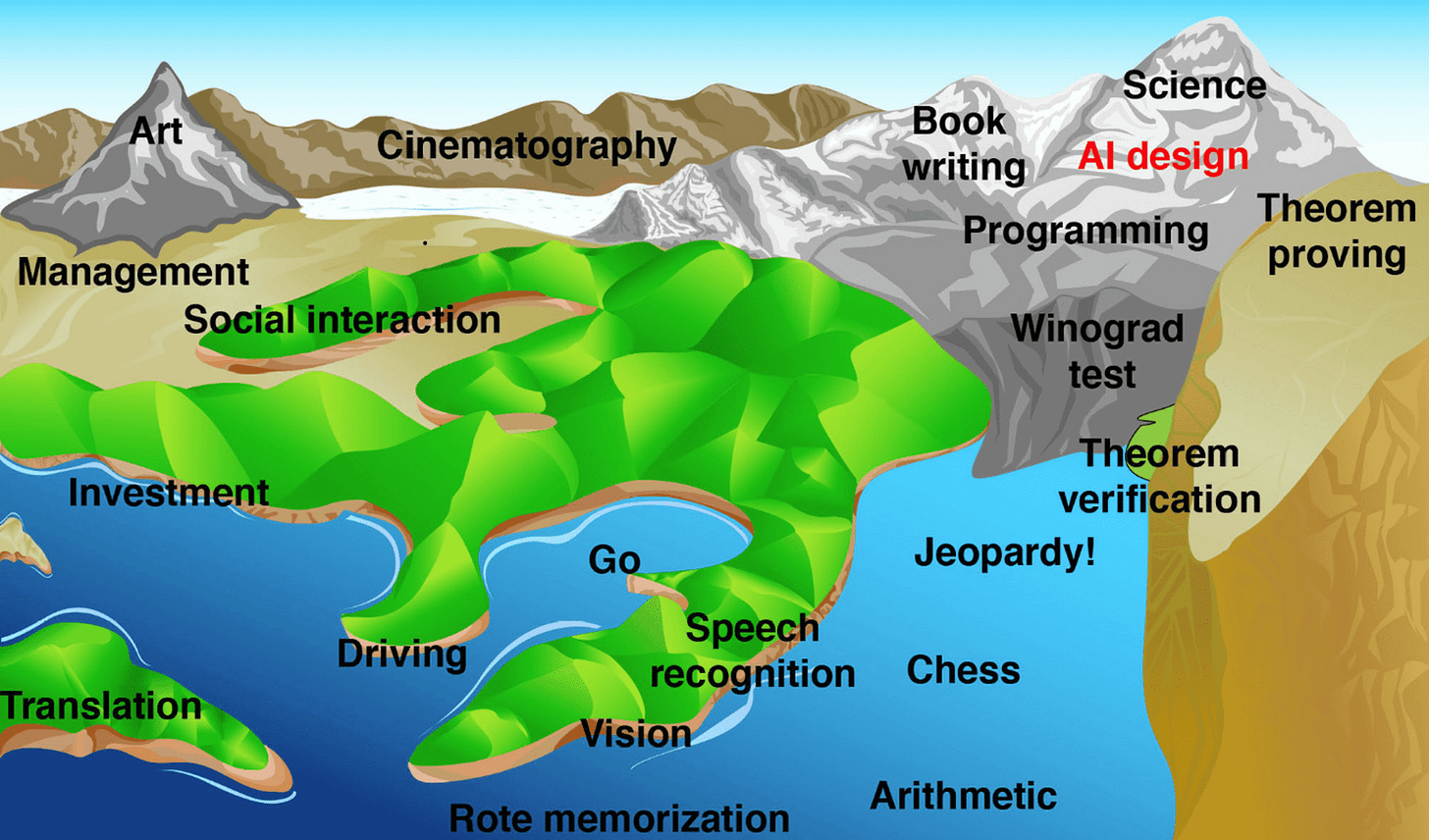

This way of thinking recalls Moravec’s “landscape of human competence” metaphor4, which imagines a rugged landscape—full of hills and valleys—populated by things humans can do, like recognizing objects and writing books. Each of these capabilities corresponds to one point in the landscape, with a given point being higher if the corresponding capability is harder for machines to do, and lower if the corresponding capability is easier for machines to do (assume we have some heuristic way to decide if something is ‘harder’ or ‘easier’). Suppose that water submerges the parts of the landscape that correspond to things machines can currently do. In this metaphor, as Moravec notes, AI progress means that the water keeps rising:

Advancing computer performance is like water slowly flooding the landscape. A half century ago it began to drown the lowlands, driving out human calculators and record clerks, but leaving most of us dry. Now the flood has reached the foothills, and our outposts there are contemplating retreat. We feel safe on our peaks, but, at the present rate, those too will be submerged within another half century. I propose that we build Arks as that day nears, and adopt a seafaring life! For now, though, we must rely on our representatives in the lowlands to tell us what water is really like.

The point of the metaphor is this: it doesn’t seem like there is some obvious class of things that AI models will never be able to do, which qualitatively separates our kind of intelligence from theirs. This is especially true if you, like me, believe that it’s reasonable to view the brain as a kind of computer. If you think that human capabilities ultimately amount to following some sequence of steps in order to transform an input into an output, then it doesn’t follow from any first-principles argumentation that AI will never be able to meet or exceed our capabilities. You can always (at least in principle, if not in practice) just figure out what steps we’re using, and then mimic them somehow.

Even if you disagree with me, and think we should define intelligence in terms of some threshold, recent history suggests that we shouldn’t define one in terms of what AI can or cannot currently do. This can change, and it sometimes changes faster than we expect. Consider that the illustration above appeared in Max Tegmark’s Life 3.0, which came out in 2017. Although there remains quite a lot of debate about this, summits like “art”, “programming”, and “theorem proving” have arguably already been at least partially submerged. The world has changed a lot in just eight years!

Capabilities and intelligence

Intuitively, “intelligence” has something to do with capabilities: the things you can do, and how well you can do them. Humans are (at least in principle) more dangerous than tigers, and this is not because we are larger or physically stronger, but because we are crafty. We can construct gadgets that tigers can’t, and we can use these gadgets to easily contain or incapacitate them.

One way to define intelligence, then, is in terms of capabilities. Person A is smarter than person B if they can do more things, or if they are better at the things person B can do. (Or some combination of those two.) I think this is on the right track. Physicist and polymath Max Tegmark agrees, and in his book Life 3.0 essentially defines intelligence in terms of capabilities (pg. 50):

intelligence = ability to accomplish complex goals

As Tegmark notes, “ability to accomplish complex goals” is a fairly broad definition. It is at least as general as “the ability to acquire knowledge”, or “the ability to solve problems”, and other similar definitions of intelligence, since each of those can be viewed as related to accomplishing a certain goal. (e.g., Your goal can be “acquire knowledge”.)

Can we sharpen this? What ‘counts’ as a goal? Should we think about one goal, or many goals? Are some goals more interesting than others?

Right after Tegmark defines intelligence in the way I just quoted, he provides a nice analogy between intelligence and athletic ability that helps us think about these questions. It’s so simple that maybe you’ve already thought of it yourself:

… imagine how you’d react if someone claimed that the ability to accomplish Olympic-level athletic feats could be quantified by a single number called the “athletic quotient,” or AQ for short, so that the Olympian with the highest AQ would win the gold medals in all the sports.

Disregarding the fact that some people do actually win an absurd number of gold medals in the Olympics, it is obviously true that there are many different ways for an athlete to be skilled. Some of them are probably even mutually incompatible: being strong enough to deadlift 500 kilograms probably means you are too bulky to win a gold medal in gymnastics. But both of these still count as amazing feats of athleticism.

Similarly, since we can imagine many possible goals—seeing and recognizing objects, navigating complex environments, efficiently chasing a moving target, understanding spoken language, beating a challenging video game, and so on—it is reasonable to think that there are just as many possible ways of being intelligent. Intelligence in this sense is often called “narrow” (or “weak” if you want to be more derogatory), since it concerns a specific goal or set of goals.

Narrow intelligence relates to the theory of multiple intelligences, a psychological theory that posits that there are many senses in which people can be intelligent. Famously, this theory has percolated through modern culture enough to produce images like these:

The opposite of “narrow” intelligence is “general” intelligence, which (according to the definition I quoted above) concerns some large set of goals. How large, and which goals? At present, it seems like we don’t really know; “general” intelligence appears to be unavoidably fuzzier than any kind of “narrow” intelligence.

While I want to mostly avoid the debate surrounding how we ought to precisely define general intelligence5 for now, it is at least worth saying that the idea isn’t totally crazy, even if it’s hard to define. First, although the use of IQ as a general measure of human intelligence is somewhat controversial, there’s also a lot of evidence to back it up. (I really don’t want to get into this now. Please don’t kill me.)

Second, it’s possible that being good at a lot of things yields a competency that to some extent generalizes, and lets you be good at even more things, even if you didn’t specifically train to do them. That is, it’s possible that being competent at accomplishing some large but finite set of goals enables you to achieve lots of other goals, since many tasks share requirements (e.g., having a good short-to-medium-term memory, being able to flexibly attend to different features of the environment, being able to adequately account for uncertainty). Maybe there’s a reasonable set of ‘basis vectors’ in the space of all possible skills. But who knows?

Given any particular kind of narrow intelligence—and hence, a specific goal—how do we measure it? What allows us to say that person A is (at least in this domain) smarter than person B, or that machine A is more capable than machine B? This depends a lot on the goal or task we’re talking about, and I will have more to say about this question when I write in the near future about “learning”. But for now, it’s worth saying that we often have continuous measures of task performance available (i.e., we can do better than “can do” versus “cannot do”), even for seemingly binary tasks, which allows us to be more granular about which agents are performing better and which are performing worse. Moreover, comparisons don’t always make sense. As the above silly picture suggests, you can grade a fish on how well they can climb a tree, but doing so might not be that useful or interesting.

In summary, “intelligence” is partly about capabilities, and in particular whether agents can accomplish complex goals. But is that all? Is it only about capabilities? I think the answer is no; we have a bit more work to do.

Constraints and intelligence

Imagine a very large6 book that tells you how to accomplish any goal that you could ever possibly pursue. You could, among other things, ask such a book for the best response to any situation. Maybe, for example, it’s a Wednesday afternoon, it’s raining outside, and your girlfriend just broke up with you. You just flip to the right page of the book, and it says something like, “get ice cream, cry a little bit, then go back to studying math”.

Is such a book intelligent? I would say: obviously yes. Since it’s a book, it can’t walk or talk, but anybody that listens to it will be able to do amazing things. They will literally be able to do anything that it is physically possible for them to do. The book tells you how to prove famous mathematical conjectures (provided the corresponding problems are decidable); it tells you how to beat the stock market; it tells you how to win friends and influence people; it tells you the answer to every homework problem you’ve ever had; and it tells you how to come up with the best possible forecast for next week’s weather. This book sounds remarkably, unfathomably intelligent.7

So why are people not worried about really big books causing the apocalypse? I think there are at least two reasons, aside from this scenario being obviously silly. The first is related to the idea of “instrumental” intelligence. (See also: instrumental learning.) We associate intelligence not just with the ability to know what to do in different situations, but also with the ability to actually do that thing. Intuitively, an agent that is good at thinking and good at acting seems smarter than the same agent without any ability to affect its environment.

The second reason, which brings us to another important notion for defining intelligence, is related to the idea of constraints. Why, exactly, can’t we physically instantiate the book I just told you about? There are many, many reasons, and all of them have to do with some combination of physical and informational constraints.

Such a book would be too physically big to ever actually exist within the confines of the observable universe, even if we could write each page of it on a different atom. And even if a very-condensed-but-useful version of it could exist, it would be too heavy for a human to carry, it would be difficult to find the page you’re looking for, its answers might be too complex to quickly understand, and it would require a lot of information that would be impossible to know by the time of its first printing.8 Maybe the future state of the world depends strongly on the result of some presidential election, for example; the book would be most useful if it either accounted for all possibilities (in which case it might be too big), or if it somehow identified the correct future outcome in advance.

All physically possible forms of intelligence, including animals (like us) and machines, face fundamental constraints like this. They occupy some finite amount of physical space; they are associated with some amount of mass and use up a certain amount of energy while operating; they can only store a finite amount of information; information must be structured in a coherent way so that it can be accessed in a reasonable amount of time; and they have limited, imperfect access to the state of the world.

Constraints are the reason the book we just imagined can’t exist, and (at least in my own view) are the reason that studying intelligence is interesting at all. In a magical world with no constraints (whatever that precisely means), there’s nothing that prevents Live-Your-Best-Life books and genies and oracles from existing.

This insight is deeper than it first appears, because constraints yield a lot of the things we typically associate with intelligence. Limits on physical size and information capacity, among others, disfavor forms of intelligence that look like the book we imagined—i.e., that just memorize some large number of input-output pairs. There are too many possible configurations of the world, and too many actions we could potentially take. These limits incentivize compression, for example by generalizing from one input-output pair to similar ones, or by memorizing a rule that summarizes the often exponentially many input-output pairs rather than memorizing the pairs themselves. Consider that you can (probably) capably add two-digit integers like 11 and 54, even though you’ve never memorized all possible sums of two-digit integers.

But compression also comes with tradeoffs. It is more memory-efficient to memorize a (sufficiently simple) rule instead of many input-output pairs, but executing the rule is more complex and time-consuming, since you need to apply the rule. In the case of adding two-digit integers, you need to add the ones place digits (1+4 = 5), then carry if necessary (no carries here), then add the tens place digits (1+5 = 6), to get the answer 65. That took some time to do. Depending on how hard it is to apply your rule, all sorts of new concerns come up, like the possibility of making a mistake. Consider that you can probably multiply five-digit numbers together in principle, but that this might take more time than multiplying smaller numbers together, and would likely benefit from pen and paper. (Although if you’re really good, you can still do this quite quickly, even in your head.)

These kinds of rules are what we mean by computations: the forms of intelligence we’re familiar with don’t simply memorize a large number of input-output pairs, but instead transform an input into the corresponding output by following some sequence of steps. The sequence of steps, or algorithm, is itself constrained in various interesting ways. For example, if there is a step that has a reasonable chance of randomly failing, it might be a good idea to execute part or all of the algorithm more than once, just in case. Concerns morally similar to this are probably at least partly why the human brain involves a lot of redundancy. In any case, the need for compression is what incentivizes sufficiently advanced forms of intelligence to involve nontrivial computations. It is due to this fundamental constraint that it’s useful to talk about the brain as a kind of computer!

Constraints are also responsible for the need for learning, for two reasons. One is again memory efficiency. It is more memory-efficient to memorize rules instead of input-output pairs; it may be even more memory-efficient to memorize rules for generating rules. The process of generating a rule is called “learning” it.

The other reason is that we generally have only a limited and imperfect knowledge of the world, and of what actions help us reach our goals and which don’t. Given this extreme ignorance, it is wise to be flexible about one’s rules for converting inputs into outputs. We might try out a rule, find it ineffective, and then decide to modify it so that it will tend to be more effective in the future. This is the essence of learning.

(It’s worth saying that it’s not always better to memorize a rule instead of input-output pairs, or a rule for generating rules instead of a rule, or a rule-for-generating-rules-that-generate-rules instead of something else. Everything has tradeoffs. In reinforcement learning, there are well-studied tradeoffs between simply memorizing the value of different states of the world, and memorizing something about how the world changes over time, and then computing values on the fly. In general, computations are more flexible, but more costly and time-consuming. See this paper for a nice discussion of how to use varying amounts of computation to solve the same problem, with different results.)

We don’t have the time or space here to adequately address the many constraints relevant for understanding intelligence, but here are a few worth mentioning:

time constraints (e.g., you want to decide on and execute your action fast enough to escape a dangerous predator);

energy constraints (you want to generate works of art without needing massive nuclear power plants);

learnability constraints (you want strategies that can be robustly learned from experience, given a reasonable amount of data and time);

developmental constraints (the complexity of animal brains must be compatible with the self-assembly that occurs over the course of development);

noise in perception, computation, and action;

and controllability constraints (you want it to be possible to efficiently command your constituent parts, so you act as a coherent whole).

Addressing all of these involves tradeoffs, which may introduce new problems. For example, exploiting parallelism—computing different parts of an answer separately—can save time and help buffer against noise, but then you need to figure out how to efficiently and accurately bring the separate bits of information back together.

Who/what is intelligent? What is intelligence?

Let’s summarize what we’ve come up with thus far.

Intelligence is probably not an all-or-nothing thing, or at least it’s probably more useful not to define it that way. Lots of things are to some extent intelligent. Even lowly organisms like bacteria ought to be viewed as intelligent, since they do many of the same things we do: they sense the world, process the sensed information, and act adaptively given what they sense. It’s true that not all forms of intelligence are equally capable or interesting—in most senses one can think of, we’re smarter than bacteria.

Intelligence is partly about capabilities (the goals you can accomplish), and partly about constraints (the things that get in your way). Different forms of intelligence involve different capabilities, constraints, or both.

Given this, I’d modify Tegmark’s definition slightly so that it reads

intelligence = ability to accomplish complex goals under constraints

The “under constraints” part is important, since it’s what makes oracles and rulebooks less interesting, and people and neural networks more interesting.

But we can be catchier than this. In the spirit of recent insight into representing intelligence in terms of an equation…

…we might write something like9

intelligence = capabilities + constraints

At least in slogan form, that’s what intelligence is.

Intelligence isn’t magic

If we view intelligence as the ability to accomplish complex goals given constraints, then it’s natural to believe that as intelligence goes up (with constraints held fixed or relaxed), we eventually hit a point where the agent in question can do effectively anything. Maybe they become so capable that to our mere mortal minds, their feats look like magic.

I kind of think this is what’s going on with the subculture of people that speculate about superintelligent AIs that can create nanobot factories to quickly build perfect robot bodies, instantly solve quantum gravity as if it were as simple as a class project, take over the world, and so on.

On the one hand, it’s true that our feats are unfathomable to a bacterium, a mouse, or even a chimp. They don’t even have the conceptual apparatus to appreciate what humans have been able to accomplish in the past ten thousand or so years. It’s certainly conceivable that to lesser intelligences, the feats of greater intelligences look like magic.

But I am skeptical. To hone in on just one example, I don’t think a superintelligent AI could solve quantum gravity by itself in some negligibly short amount of time, especially if it were placed into the world a thousand years ago without a modern knowledge of physics.

The people that have studied the natural world within the past three thousand years were not stupid. They were wrong about many things, but they were not unintelligent. Aristotle was wrong about a lot of things; the medieval philosophers were wrong about most things; and Isaac Newton was wrong about a lot of things. But, and I cannot emphasize this enough, they were not stupid or irrational. They were working hard within the intellectual frameworks of their time, and with the limited amount of data they had available.

Why, then, didn’t they discover Newtonian mechanics, or quantum mechanics, or that the Earth revolves around the Sun and not the other way around, much earlier? Why, if not due to their irrationality? That’s worth an essay of its own, but the short answer is that science is really hard.

When I say “hard”, I mean “computationally hard”. The space of plausible hypotheses is so large that it takes an extremely long time to search through. Moreover, experiments often can’t reliably distinguish between many even qualitatively different hypotheses. (See also: identifiability.) Consider models of the solar system. It wasn’t just that people were stupid and superstitious, and simply couldn’t accept that the Earth revolves around the Sun—although that was certainly part of the issue in some times and places.

Rather, a model where the planets and stars orbit the Earth, and a model where they orbit something else (like a “central fire”), fit about equally well. In fact, the history is much messier and weirder than I originally thought: Copernicus’ theory did involve epicycles on top of the Earth revolving around the Sun, and didn’t originally fit the data better than the Ptolemaic theory did.

High intelligence means you can do as well as it is possible to do given your constraints and the information you’re given, but this isn’t the same as being successful at every task with 100% probability. Some tasks are just really hard, and even in the best case you tend to fail at them, or take a really long time to complete them.

(See also: the concept of the ideal Bayesian observer. In many perception tasks, we can imagine an agent that does as well as possible given environmental and perceptual noise. Noise prevents them from doing perfectly well, and this observer’s ‘performance ceiling’ can be made arbitrarily low by making the amount of noise sufficiently high.)

Cryptography supplies another class of examples. Factoring a large prime number, or finding the discrete logarithm of a point on an elliptic curve, is something that even the best possible algorithms take a long time to do. This is why we use cryptographic problems to secure sensitive information, for example during banking transactions.

Whether you think sufficiently intelligent AI can take over the world and solve the ultimate scientific problems essentially amounts to whether you think that the computational hardness of those problems is more like the hardness of factoring large prime numbers, or like the hardness of multiplying numbers. I tend to think science is really really hard, but smart people probably disagree with me. I’m less sure about how hard it is to take over the world, but that seems pretty hard too.

I’m not an aerospace engineer, but if Wikipedia is any indication, maybe the more precise way to say this is: they built the first engine-powered, heavier-than-air aircraft capable of sustained, controlled flight.

Have we really achieved artificial general flight? It’s true that planes and drones still can’t fly with the same flexibility and energy efficiency as, say, hummingbirds. But I don’t think this matters. The point is that we can effectively fly as far as we want, as long as we want, and in more or less whichever direction we want; it’s okay if birds and other flying animals definitely beat us in some respects.

There are, of course, other reasons to be skeptical that a given feat is evidence of high intelligence. I’m just saying that your argument should not hinge on being able to precisely define “intelligence”. Being able to precisely define anything is hard, so this kind of reasoning can be used to argue for skepticism about almost anything.

I first learned about this metaphor from Max Tegmark’s Life 3.0, which (at least given what I’ve read so far) I highly recommend.

At this stage, I should say: in fairness to Jascha, he wasn’t really complaining about people wanting to define “intelligence”. He was mostly complaining that people unsatisfied with our current definitions of “general intelligence” shouldn’t let their reservations with our definitions prevent them from seeing that progress is happening.

What I really mean here is absurdly, enormously, unrealistically large. But forget about that for a second.

If we wanted to invoke Tegmark’s definition, we could say that this book has the goal of “providing its reader with the ability to accomplish any goal”, and is hence intelligent in that sense.

It would also, unfortunately, take an infinite amount of time and energy to print.

The plus functions more like an “and” here than anything else. I’m not saying more constraints equals more intelligence, or something equally weird.

Great post, and I have similar intuitions to the ones you lay out in the final section about the nature of intelligence. Some problems are indeed just *really hard*, no matter what level of "intelligence" you have. I don't expect a fast takeoff with killer nanobots in our near future.

Gwern has a great piece arguing against this intuition (https://gwern.net/complexity) which is an interesting read to challenge your assumptions. But I remain unconvinced.

One example he gives is that "a logistics/shipping company which could shave the remaining 1-2% of inefficiency off its planning algorithms would have a major advantage over it's rivals." Fundamentally, that's still describing an advantage in the context of our institutions, markets, and manufacturing process. The situation being described is less "AI reaches the singularity and immediately ascends, discarding our institutions and releasing paperclip-manufacturing nanobots," and more, "AI slowly outcompetes us in more and more domains until there is nothing left for humans to do."